At first glance clothing donations seem like a triple win. First as the donor, you are getting rid of unwanted clothes; second, you are diverting them from the landfill; and third, your clothing donations are given a second life in someone else’s closet. However, like many other things, it is not as simple a concept as it seems. In fact the second hand clothing industry is very complex.

By definition, sustainable consumption is the ability of current and future generations to meet their needs without causing irreversible damage to the environment or loss of natural systems. But in order to create meaningful progress towards sustainable consumption, we must also address our disposal habits.

Unfortunately, we still know very little about what happens to our clothing after we’re done with it, and how to dispose of it – sustainably and ethically.

Where Does it All Go?

The general practice of secondhand clothing (SHC) redistribution is complicated, long, and intensive. 76% of Canadians donate clothing through donation bins, thrift retailers or charity collectors. But only 50% of this clothing ever makes it to the SHC racks and of that only 25% is sold to local customers. What isn’t sold in stores is sold or donated to a local sorter or grader. Sometimes this sorting and grading happens locally, and other times, for cost efficiency, it is shipped overseas to be sorted and graded there.

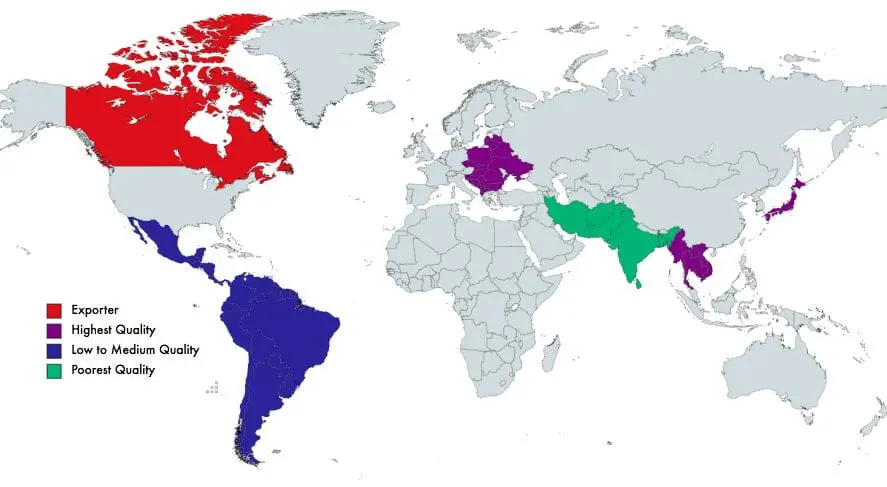

The items are first sorted into a number of categories, like clothing, footwear, or stuffed toys. The quality, brand name and style of our used clothing is the biggest influencing factor as to where they end up. This is how the grades are classified:

- Highest quality: Sent to East Asia and/or Eastern Europe

- Low to medium quality: Sent to Latin America and/or Sub Saharan Africa

- Second poorest quality: Diverted to South Asia

- Also known as shoddy – poor quality materials down-cycled into rags for industry or are broken down into fibres when possible

Once in the destination country, it becomes difficult to track where this used clothing goes. As containers arrive in the various destination ports, the bales are purchased by shop owners who sell through to local customers in various market stalls. After you consider a 2-4% human error with respect to sorting according to condition, style and brand of a garment, it is in the best interest of the exporter to make sure that only quality materials are in that bale. If not, they risk losing future business with that buyer. Even a single stall owner who receives a bad bale of stained or torn garments can negatively impact whether that exporter can continue doing business in that market. The exporter wants to ensure they can continue to sell bales particularly given their company name is clearly marked on each one.

The Crisis of Stuff

Developing countries that receive SHC from the Global North have integrated it into their local economy. However, SHC is not part of the formal global economy and is therefore most often completely unregulated. Despite being a charitable exercise for consumers in the Global North, SHC is processed as a commodity within the Global South. For example, SHC cartels and illegal street trading have emerged, caused by a gap in regulations and a lack of formal economic opportunities. In addition, the practice of international clothing donations has had an unintended impact of preventing foreign textile markets from being lucrative and sustainable.

For these reasons we have seen complex and long term trade negotiations develop between exporting countries who rely on importers to absorb clothing, and some importers who have asked for donations to stop. SHC, by this logic, is very important to the formal economy despite being actively excluded, and this is reflected in decades worth of policy changes that have ultimately worked to not benefit importer states.

Benefits to SHC

Locally, there are benefits to clothing donations. They provide additional revenue streams to charitable organizations who need funding for social programming like Diabetes Canada, who is contracted by Value Village to operate donation bins, and customers have access to great products at a fraction of the price.

Locally, there are benefits to clothing donations. They provide additional revenue streams to charitable organizations who need funding for social programming like Diabetes Canada, who is contracted by Value Village to operate donation bins, and customers have access to great products at a fraction of the price.

It is also a great way to (mostly) divert would-be textile waste from landfills since only about 5-10% of what is collected and sorted in Canada is said to end up in landfill locally.

There are also many groups doing great work to reduce our global textile waste, and to correct the inequities of the industry. Bank & Vogue is one such example. An exporter of second hand clothing, they also own popular UK thrift retailer Beyond Retro who have upcycling collaborations with brands like Converse. Recently they are partnered with Sweden’s Renewcell to supply them with used denim feedstock for recycling.

such example. An exporter of second hand clothing, they also own popular UK thrift retailer Beyond Retro who have upcycling collaborations with brands like Converse. Recently they are partnered with Sweden’s Renewcell to supply them with used denim feedstock for recycling.

Ultimately, for now, clothing donations to charities or other organizations are the best solution, because at the end of the day, they keep reusable textiles out of landfills, and facilitate the recycling of those textiles that are not fit for reuse.

Working on Fixing the Problem

While we recognize that clothing donations divert textile waste from landfill or incineration, the best thing you can actually do is to stop buying things that you don’t actually need!

Fast fashion, and the subsequent consumption habits that have evolved as a result of low quality, inexpensive clothing drives this problem (which I wrote about back in January). Take a moment to think about what you’re buying new and make sure it’s something that you really love and will last a long time.

When donating to small charities in your community only donate what actually meets the community’s needs. Research the organizations you’re interested in donating to and see what items they are looking for most and what they’ll do with that clothing. Handing a bag of summer clothing to a small charity in the middle of winter isn’t likely to help anyone.

Larger charities and thrift retailers are more equipped to manage unsellable items because they sell or donate these items on to a sorter or grader. Mark your donation bag with “Rags” or something that will clearly let the sorter at the retail store know it should go straight to the non-sellable pile.

We have the responsibility – as consumers who actively engage in the fashion system – to do the work. So let’s start doing it.