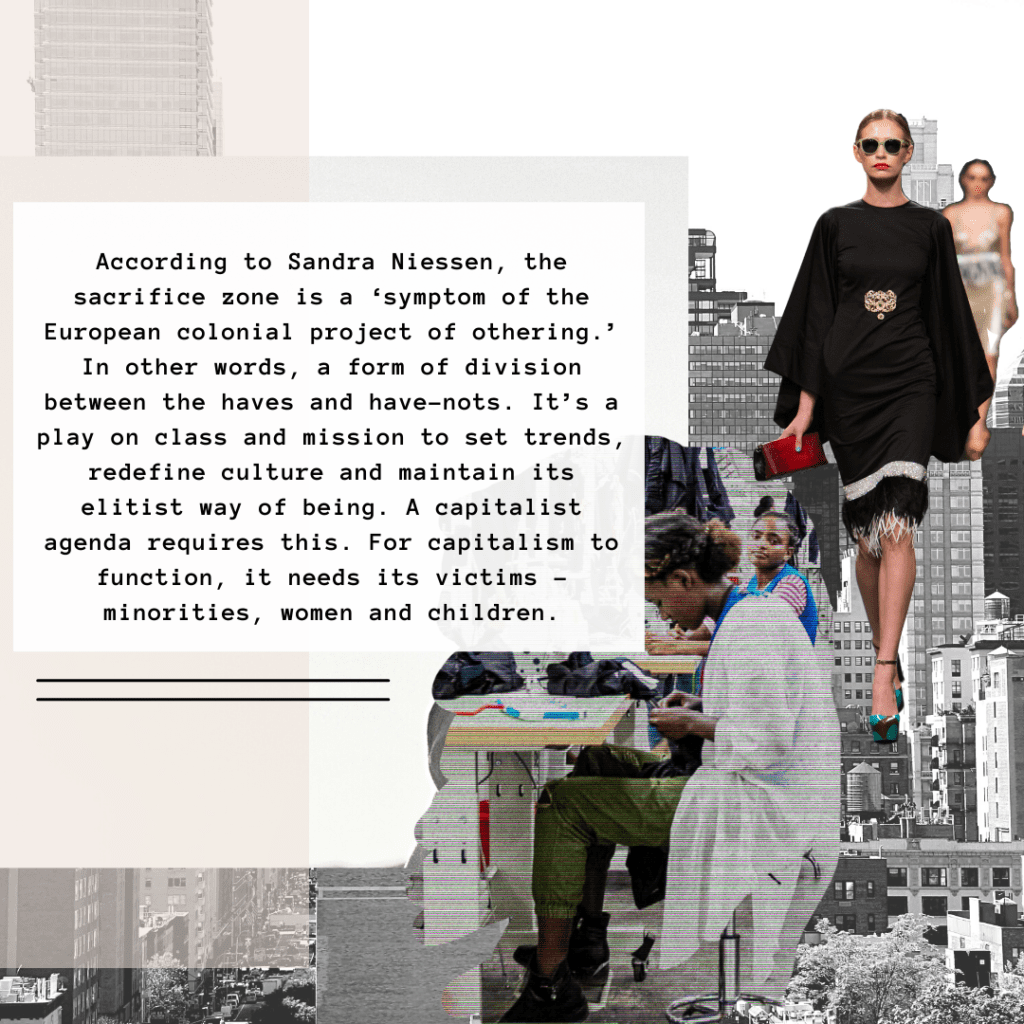

Anthropologist Sandra Niessen believes that the fashion industry has created a sacrifice zone that runs so deep it forms complicated predicaments in obscure ways. Niessen’s article: Fashion, its Sacrifice Zone and Sustainability delved into the layers of policy and practices that undervalue workers on the ‘lower end of the fashion pyramid scheme; which capitalizes on mostly women of colour in third world countries.’ Compiling a myriad of indicators such as identity politics, white supremacy and exclusivity, fashion, according to Niessen, is a ‘symptom of the European colonial project of othering.’ In order words, a form of division between the haves and have-nots. It’s a play on class and mission to set trends, redefine culture and maintain its elitist way of being. A capitalist agenda requires this. For capitalism to function, it needs its victims – minorities, women and children. However, since there is enough monetary value for everyone who works in this industry to reap its benefits, what prevents us from moving in an agreeable direction? Short answer: the power dynamics. It’s this schism between us vs them. Therefore, in this case, how do we ensure that when discussing the problematic plague of fashion, the conversation goes beyond sustainable practices to protect the planet such as the place of purchase, the production of the clothing, the material or consumption habits, and incorporate cultural appropriation, racial justice, and this colonial agenda?

Sacrifice Zone

Niessen explains that the colonial legacy of fashion interferes with sustainable fashion production, leaving no room to consult alternative systems for insight into how to ease the fashion problem. This fashion legacy was mirrored based on principles to build wealth at the expense of exploiting people of colour, and the dominating decision-makers are white. It is not far-fetched to revel in the idea that the fashion pyramid scheme is a form of modern slavery since the majority of black and brown people lose their culture in their clothing after they are reproduced and marketed as mainstream fashion.

According to the Clean Clothes Campaign, 60 million garment workers are deprived of a living wage, access to health care, safe transportation, adequate food, spending time with family, or getting a proper education. Instead, their lives involve being overworked and producing clothes in an unrealistic manner to meet the demands of fashion brands who capitalize on fast fashion and their money-grubbing wishes—leaving garment workers to live below the poverty line. Statistics Canada reports that the total annual turnover of fashion retailers is 28 billion CAD, with retail companies Gildan Activewear (4.8 billion CAD) and Hudson’s Bay (3.1 billion CAD) leading with the highest revenue to date.

The sacrifice zone targets more than just the stark differences in wage gaps between fashion brands and garment works or how it is one of the world’s major polluting industries affecting us at a global level, but it’s careless whispers towards cultural loss, the dividing line between certain voices that fight their way through this industry, and institutional racism that is creating a wave of the different facets of what it means to sustain something.

A western perspective sees garment workers as those receiving an income regardless of how much is earned and the politics that reflect poor living conditions in these environments. Fashion brands indulging in this business model have managed to sustain this type of production, despite the number of resources or campaigns such as Who Made my Clothes, #PayUp, or #NoNewClothes, that provide strategies on how to dissociate from corrupt practices. The lack of understanding and accountability illustrates systemic erasure and culture divides. Garment workers are seen as a convenience, considered as dispensable and exploited for economic gain. This ongoing dilemma tells garment workers that they are not worthy of life. And we need to face the fact that racism is the foundation of these principles and practices.

Writer Lolita Maesela points out in her article, A Wave of Designers Is Changing the Conversation Around Cultural Appropriation, “though skilled artisans in countries like India are responsible for some of the most exquisite detailing in fashion’s couture creations, their work has been routinely underpaid, undervalued and uncredited by the fashion industry, which has instead promoted a western-centric view of what should be considered luxurious.” Therein lies the problem of redefining culture in a way that refutes history, traditional practices and even religion. Slow fashion promotes the skilled craft of artisans. It aims to rescue, revive and preserve. But finding avenues to protect this way of creating in a fast-paced fashion exercise is challenging to say the least. COVID-19 had seeped into these villages, which has resulted in an economic downturn after the closure of factories.

Where are we headed?

There is a long road to recovery and inclusivity in the fashion industry. A fair business model is a people’s call, and it aims to protect garment workers as well as designers, activists, writers, photographers, administrators, managers, etc. Dominique Drakeford, a nontraditional environmental educator, is steering the direction of the conversation that is being ignored by some of the decision heads at the top of the fashion pyramid scheme. “Before we even get to sustainability and fashion, we have to look at how sustainability and environmentalism have been portrayed. The dominant narrative has been constructed and informed by whiteness. We have to understand that that’s been oppressive throughout the whole trajectory since inception. We’ve been sacrificed within the mainstream sustainability space. So subsequently, when you get to fashion, it’s the same thing.”

Attention to diversity and inclusion goes far beyond gender and race but the differences in our thinking and conceptualizing our ideas to dismantle the fashion sacrifice zone. However, it is uncomfortable for people of colour to be in rooms where the conversation about institutional racism is not being had. Writer Kayla Holliday quotes in her article, Why the Next Part of the Sustainable Fashion Conversation Will be About Racial Justice, Aurora James, founder of sustainable luxury brand Brother Vellies and creator of the 15 Percent Pledge who states that “for a long time, sustainability has been a problem that’s been easy for people to look outward to try to fix. There’s been a lot of companies that are very quick to talk about sustainability but not quick to talk about racial equality. But at the same time, we also know that climate change most directly and most quickly impacts Black and Brown communities.” The road to recovery means acknowledging this fact.